The billion dollar note on the floor

Published

Theory of technological readiness and the timing of startups

In Timing Technology: Lessons From The Media Lab, Gwern highlights an interesting phenomenon. Many visionaries demonstrate remarkable prescience about what a future transformative technology will look like (e.g Mobile Phones, VR etc), but are seemingly unable to capitalize on this foresight.

This inability stems from their failure to accurately predict when a

transformative technology will happen. Given that the return on investment from startups follows a power law, this means if you don't

back exactly the right unicorn horse, you miss out on ~all the gains. The power law explains a common phenomenon

seen in venture, termed "stampeding". When it becomes clear that a sector is experiencing explosive growth, both

entrepreneurs and VCs will flock to it, but a few lucky ones will capture all of the value. This stampeding effect is a well known,

often derided characteristic of venture. However, there is a second, less often discussed failure mode, namely leaving a

billion dollar note on the floor.

Starving a transformative technology of investment past the point of commercial possibility means VCs are leaving value on the table. The paragon of this failure mode is Oculus VR. Palmer Luckey was 18 years old, had no VC funding, and lived in a camper van on his parents' drive when he developed the first Oculus prototype. Oculus went on to be sold to Facebook for $2.3B. How was it possible for a unicorn to be created by a teenager with no industry experience or capital? I believe it was something I'm terming "Orthogonal Technology Development".

Developments in the consumer mobile industry (Battery capacity, Display resolution etc) enabled consumer VR to be created for a price palatable to consumers. Luckey had no capacity to do ~any R&D himself, he simply struck when a confluence of external developments reached the required functionality. The amount of funding available to early stage startups precludes any hope of doing significant fundamental R&D on Input Technologies. This means that successful startups must wait for developments in an orthogonal field to enable new capabilities for them to capitalize on. A venture fund tracking fundamental input technologies, maintaining a database of prior startups pursuing good ideas, and understanding government R&D (typically the earliest exploratory R&D), will have an enormous advantage.

Good startup recipe

...a good idea will draw overly-optimistic researchers or entrepreneurs to it like moths to a flame: all get immolated but the one with the dumb luck to kiss the flame at the perfect instant, who then wins everything, at which point everyone can see that the optimal time is past.

— Gwern

There are some interesting commonalities among BIG startup ideas:

- Due to the Power Law of venture / Babe Ruth Effect, you need the TAM to be large enough to be the fund leader. Determining the TAM is challenging, as truly transformative technologies create new markets (i.e Uber reduces friction of getting a taxi, so demand increases).

- All the best ideas have been tried before, if your idea has not been seriously tried before by the government or industry, it is almost certainly not a good idea. Multiple discovery is the norm, not the exception.

- Given the idea has been tried before, the startup needs to have failed due to uncontrollable external factors (e.g Battery capacity too low, Macroeconomic conditions, Poor management etc).

- The landscape needs to have changed such that the external factors causing the prior failure are no longer valid. Investment in an orthogonal field must have reduced the price / improved the capabilities of prerequisite technologies.

A systematic database should give funds a starting point when evaluating startups, or a way of deciding if it's the right time to incubate a startup in a particular sector.

Case Studies

We've determined that understanding Input Technologies and obviously good ideas (bottom up vs top down) is a useful exercise for both VCs and entrepreneurs. We shall apply this theory to prior ventures to further validate the approach.

Pets.com

Let's begin with the canonical example of 90s hubris - Pets.com. The founders of Pets.com were thwarted by 2 key things: the number of people on the internet, and the proportion of those comfortable with transacting over the internet.

In 1999 only 113M people were using the internet, and an unquantifiable but certainly smaller fraction of those were comfortable paying for products online. Does this mean that selling pet specific products over the internet is a bad idea? Luckily the universe has run the experiment for us. Chewy.com is exactly the same idea, only founded in 2010 when 288M people were using the internet, and they'd all paid for things online. Fundamentally, there was nothing the Pets.com founders could have done to change this, save for a parallel venture in internet infrastructure or online payments. They were doomed due to factors outside their control.

SpaceX

What was once the realm of governments became the realm of a private company. SpaceX has done this twice now, both with launch capabilities and with Starlink.

Starlink is the primary revenue driver of SpaceX, but was not the first attempt at satellite constellation for global internet (another obviously good idea). It was attempted before by Motorola with their Iridium constellation. Mapping and understanding when the prerequisite technologies make it commercially viable (in this case $/kg to orbit) is key to derisk investments.

The creation of a transformative startup is a virtuous act, as it itself is a prerequisite for the next generation. What startups are enabled by $/kg to orbit dropping by another order of magnitude with Starship?

Tesla

An all electric car is not a new idea. Below is a Popular Science magazine cover from September 1975.

So why did it take 40 years to get an electric car people actually wanted to buy? JB Straubel realised that the time might be ripe for the first consumer electric car when he was helping out with the Stanford Solar Car Challenge.

Straubel and the solar team kept fixating on one topic. They realized that lithium ion batteries ... had gotten much better than most people realized. Many consumer electronics devices like laptops were running so-called 18650 lithium ion batteries. ... "We wondered what would happen if you put ten thousand of the battery cells together... "We did the math and figured you could go almost one thousand miles. It was totally nerdy shit ... but the idea really stuck with me.

Elon Musk Biography — Ashlee Vance

This realization went on to be codified in "The Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan (just between you and me)", which is truly one of my favourite documents of all time. If you do not have this level of clarity on why for fundamental reasons your startup is going to win, I don't believe you can have the conviction to push through the inevitable dark times. Treat that document like the Constitution and refer to it in times of hardship.

Netflix

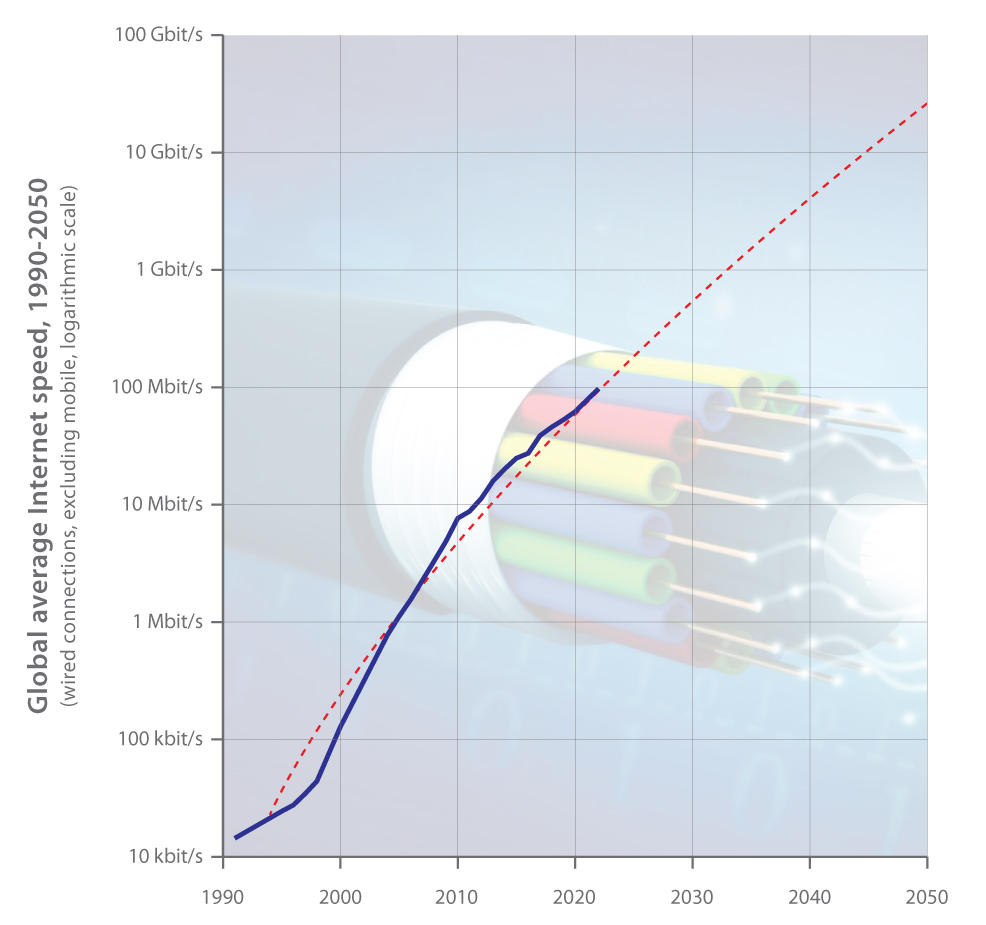

Although beginning as a mail order DVD service, the founders of Netflix one day envisioned distributing media over the internet, hence the name. The fundamental prerequisite for this was internet bandwidth (both cost and quantity). If Netflix started distributing video over the net too soon, their bandwidth costs would burn through all their capital, too late and they would miss the boat. Netflix launched WatchNow in January 2007, when the average global internet speed was ~2.5Mbps. This just so happens to be the minimum viable speed for streaming 720p video, a curious coincidence.

By 2011, Netflix had become by far the largest user of peak bandwidth on the Internet. Understanding within a ±5 year range when it would be possible for video media to be distributed over the net at palatable costs would have made identifying investment opportunities in this space much lower risk.

The Checklist

Humans are very error prone, which is why in high stake environments checklists are fundamental. In his post, Technology Forecasting: The Garden of Forking Paths, Gwern outlines a Munger-esque checklist for technology forecasting:

- Are there any hard constraints from powerful theories like thermodynamics, evolution, or economics bounding the system as a whole?

- Breaking down by functionality, how many different ways are there to implement each logical component? Is any step a serious bottleneck with no apparent way to circumvent, redefine, or solve with brute force?

- Do its past improvements describe any linear or exponential trend? What happens if you extrapolate it 20 years?

- What experience curves could this benefit from in each of its components and as a whole? If the cost decreases 5% for every doubling of cumulative production, what happens and how much demand do the price drops induce? Are any of the inputs cumulative, like dataset size (eg. number of genomes sequenced to date)?

- Does it benefit from various forms of Moore’s laws for CPUs, RAM, HDD, or GPU FLOPs? Can fixed-cost hardware or humans be replaced by software, Internet, or statistics? Is any part parallelizable?

- What calibre of intellect has been applied to optimization?

A systematic application of checklists like this (perhaps augmented by AI) can further derisk investments.

Designing a systematic VC fund

One idea is that a VC firm could explicitly track ideas that seem great but have had several failed startups, and try to schedule additional investments at ever greater intervals, which bounds losses (if the idea turns out to be truly a bad idea after all) but ensures eventual success (if a good one).

— Gwern

Although, "ideas that seem great" will be steeped in hindsight bias, I believe that an attempt should be made to structure a platform for VC funds / entrepreneurs that is designed as follows:

- Explicitly tracks developments in Input Technologies, like batteries (Wh/kg, Wh/$), bandwidth (Average Mbps per household), computation (TFLOP/W, TFLOP/$), launch capacity ($/kg to orbit), sequencing cost ($/Mb of DNA).

- Maintains a historical record of previous startups attempting to create an obviously good startup idea (e.g humanoid robotics, pizza delivery by app etc).

- Using the above 2, build a set of trigger conditions for obviously good ideas (e.g 150 Wh/kg + 100$/Wh for electric cars). Then, when the opportune window arises, the fund can back multiple entrants or cultivate the right entrepreneur with the idea.

Being aware of the "technical window of opportunity" does not supplant VC understanding of the broader market, but provides a bound to ensure positive expected value.

Interested? See it in action